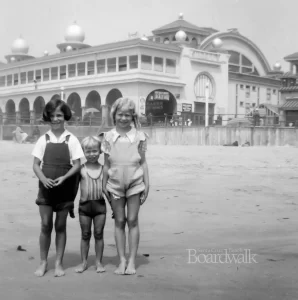

A while back, a photo was contributed to our Boardwalk Memories webpage that puzzled me. Behind a 1920s image of Ray O‘Reilly and his girlfriend Victoria, relaxing against a Boardwalk railing, a structure sits far in the distance. I had no idea what the edifice was. Until recently when a series of hand drawings, dated 1927, surfaced in our archives. They depicted the construction and operation of a Shoot-the-Chutes ride at the Boardwalk. The old photo began to make sense. Thus began a fascinating journey to uncover the history of an area of the Boardwalk that remarkably had been lost to our present-day collective memories.

From its earliest years, Boardwalk leaders sought to extend our park’s footprint eastward toward the San Lorenzo River. Visitor momentum in the Roaring Twenties supercharged this interest. Finally, in 1928, a bathhouse and outside dance arena, dubbed “Mission Dance,” were constructed, extending the Boardwalk out almost to the river’s mouth where it empties into Monterey Bay. I’ll say more about those entertainment activities in another blog.

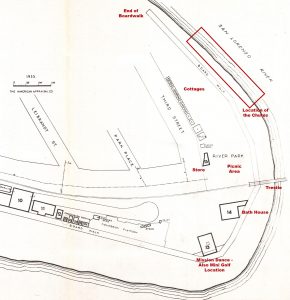

Seaside Company principals were also eager to develop their property along the western bank of the river. In 1928, the Boardwalk walkway was extended northward, under the railroad trestle, another 800-feet or so. This appraisal map provides a good visual of how the river area looked during this time of expansion and development.

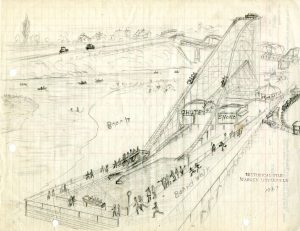

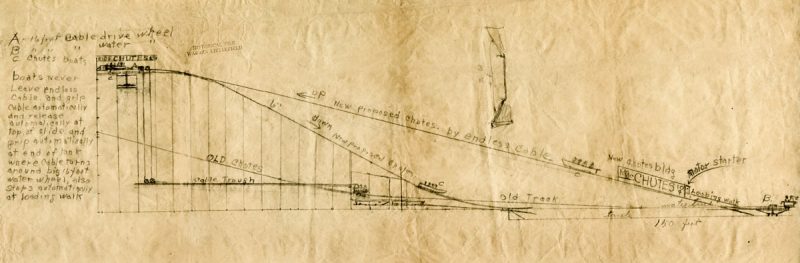

This northern river-bounded area became known as River Park. Today it’s the southern part of our River Parking Lot. I now suspect those 1927 hand drawings were used by a concessionaire named Stanley Kohl to obtain permission to erect a Shoot-the-Chutes as that area’s primary attraction.

Chutes rides appeared on the national amusement scene in the late 1880s and rapidly rose in popularity. Between 1904 and 1929, at least three Chutes operated for a time in nearby San Francisco and Oakland, California.

A forerunner of today’s flume-style rides, a large flat-bottomed boat would be hoisted up an incline to quickly slide down a greased ramp and skip along a body of water, thrilling its occupants. Once they had disembarked, a new complement of adventure-seekers would board. Then the employee “captain,” who accompanied the party of “daredevils” in the craft, maneuvering the boat back towards an incline ramp where a steel cable would pull it up to the top of the Chute’s structure to repeat the experience.

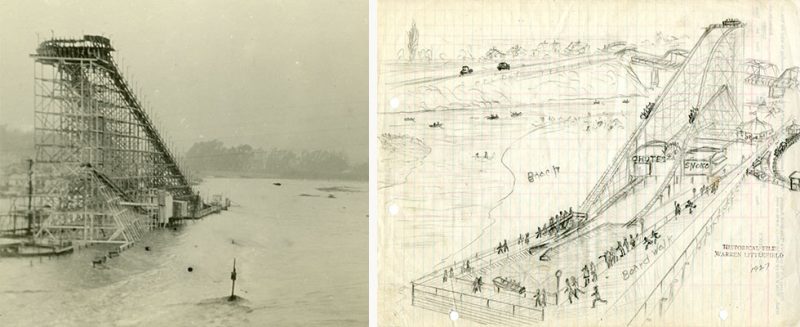

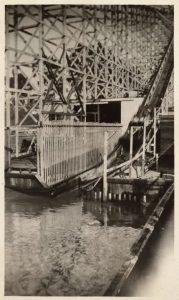

Once given a go-ahead, Kohl began construction of his Chutes’ structure in April 1928. By June, it was ready to operate. The Chutes used the river as its runout pond. An electric motor lifted Chute boats on an incline topping out at 50-feet. They then slid over 300-feet into the river lagoon.

Once given a go-ahead, Kohl began construction of his Chutes’ structure in April 1928. By June, it was ready to operate. The Chutes used the river as its runout pond. An electric motor lifted Chute boats on an incline topping out at 50-feet. They then slid over 300-feet into the river lagoon.

A merry-go-round, a seaplane-deluxe ride, consisting of three planes that swung out and up for thrills, a picnic area for several hundred picnickers, a kiddie play space with swings, teeter-totters, slides and rings, a restaurant, some beach cottages, and a few concessions rounded out the River Park development. Concessions served snokos, a forerunner of shaved ice, and puffles, multi-colored flaky, fruity chips – fun foods of that era – along with other crowd-pleasing items.

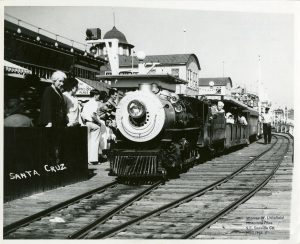

Up to that time, beach activity had centered and clustered around the Casino, Plunge, and Pleasure Pier complex at the Boardwalk’s western end. A way was needed to expedite public movement to its burgeoning eastern development. To this end, Kohl inaugurated a new miniature railway to carry visitors between River Park and the concentration of folks near the Casino complex. Track stretched between the foot of the Pleasure Pier to a new River Park station for a round-trip of about 3,300-feet. Interestingly, near where the Giant Dipper station is today, the rails lowered to sand level. The mini railway continued its journey toward the river, under the Boardwalk and the railroad trestle, before arriving at its River Park station.

By mid-July 1928, the Santa Cruz Evening News reported that River Park was as famous as the rest of the Boardwalk.

The Chutes and miniature train’s financial performance that first season buoyed concessionaire Kohl’s desire to enhance his structure’s thrill appeal. There was only one thing to do – build bigger and go higher! Kohl planned a more prominent structure for the next year. His new design had its own runout water pond, freeing his ride from ocean tidal influences on the river.

So eager was Kohl, that a winter storm in 1928 which wiped out a section of his railroad tracks, did not derail his enthusiasm. In February 1929, a crew of eight men began working on modifying and enlarging the original Chutes framework. By the end of June, the re-engineered Shoot-the-Chutes was complete. It re-opened on July 3.

This new attraction dwarfed the former structure. The boat drop from the top of the lift was 80-feet – nearly double the old chutes – and 10-feet higher than the Giant Dipper’s tallest hill. The massive construction measured 360-feet in length. Three boats were attached to a continuous cable and hoisting apparatus. Eight passengers and one operator maxed out each craft. Each boat slid downhill to hit the water at a reported speed of 60 miles per hour, splashing into a 40-foot by 18-foot cement tank of water. After being filled by river tidal action, the tank was kept at a constant level.

The bottoms of the second generation of Chutes’ boats were equipped with fins to slow their speed over a shorter distance. Once stopped, passengers disembarked, and a new group of thrill-seekers stepped in. As with the former structure, the boats then picked up the cable and were hauled up the lift, but this time, pulled by two 18-foot wheels, one at the top and one in the water tank. The contraption was powered by a 75-horsepower electric, all-gear motor.

A new lighting system with several thousand incandescent lights was strung along the Boardwalk the summer of 1929. The light string stretched along the River Park walkway, too, and 500-lights were added to the Chutes structure itself.

At summer’s end, Seaside Company President R.L. Cardiff reported that business had been good at all the company’s holdings. The most significant investment in the 1929 season had been Stanley Kohl’s Shoot-the-Chutes and River Park. He hinted that plans were afoot to add “box ball games, bowling, and many forms of outdoor attractions” to that area for the coming year.

However, Cardiff’s optimism was foiled by the fateful stock market crash of October 29, 1929. The resulting economic slowdown did not bode well for several river-area attractions. In April 1930, Seaside Company advertising still promoted the River Park picnic grounds, boating, and the River Bath House. No mention of other river area activities appeared. Then in June that year, the paper reported the demise of the river dance area. The “Mission Dance” phenomenon had lasted only two years and morphed into the Boardwalk’s first miniature golf course.

Regarding the Chutes, photographic evidence revealed the structure in place at the time of a storm and river flood in December 1931. Then, on October 4, 1932, the Evening News announced the chutes structure was being dismantled. Surprisingly, it quoted a Seaside Company official stating the ride had not operated for two years. There were no definite plans for any more concessions along the river.

Hence, the Chutes operated for three years, from 1928 to 1930. The Santa Cruz Sentinel reported the ride “never brought paying dividends to the owners.” Ultimately, it proved too distant from the center of Boardwalk concessions near the Casino. I suspect repairs from winter storms inflated maintenance expense and low ride capacity limited his summer revenues too.

As far as I can determine, Kohl continued to operate his train until 1933, when the Seaside Company took over the ride, renaming it the “Sun Tan, Jr.”

If you or your family has any recollection of River Park and the Chutes, please let me know.

-till next time –

Ted