When I swam in the plunge in the late 1950s and early 1960s, I remember staring up at the trapeze bars and rings hanging silently from the ceiling. Empty platforms were perched above the building’s balcony level on the upper west and east walls. All were hushed reminders of the days when an incredible water spectacle occurred in that building – the water carnivals!

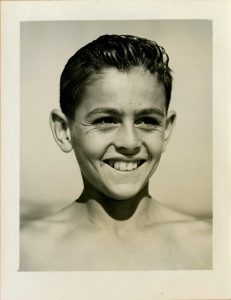

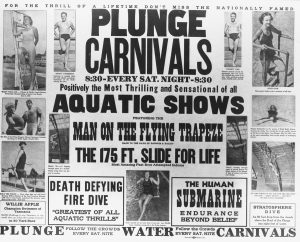

The Boardwalk’s Salt Water Plunge Water Carnivals are legendary in our park’s history. Much is recorded about these feats in the Boardwalk’s Centennial Book, Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk: A Century by the Sea. Our archives abound with news clippings from the staged shows that occurred between 1927 and 1945.

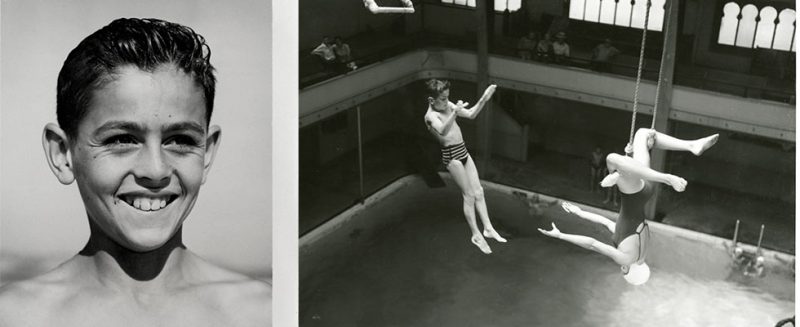

I did not appreciate the exhibition’s full scope until I met one of its performers later in life. Two years ago, our archivist Jessie Durant and I sat down with Fred Quadros, Jr, and his wife, Marilyn. In the early 1940s, Fred was one of the carnival’s youthful stars – an “aquabrat” as they were called. There were “aquabelles,” too.

Meeting Fred came by an unusual sequence of events. His son had driven by the Boardwalk and spotted a young likeness of his dad emblazoned on some cyclone fence wrap during a construction project. He promptly had his dad check-in at the Boardwalk to see what that meant. Fred’s inquiry led to our interview. He brought a scrapbook with him of never-before-seen photos, documents, and clippings that told more of the water carnival story. It was a fascinating conversation that I draw from for this blog.

Fred was 11 to 14-years old during his water carnival escapades in the early 1940s. He first took swimming lessons in the plunge at 9-years of age and dramatically overcame his fear of water. Several years later, he and a few local kids passed an audition for the summer swim and aerial fest. His natural daredevil athleticism and guts had something to do with it, for sure.

Like many adolescent kids of his day, Fred was a regular at the Boardwalk. He worked in a variety of positions before and during his water carnival years. From being a plunge “locker boy” to working at the Looff Carousel, Walking Charlie game, and setting pins at the duckpin alley, Fred was well known in Boardwalk circles.

He rode the waves at the San Lorenzo River mouth, using boards borrowed from the plunge. He could easily be picked out of the pack in his “bumblebee,” yellow-and-black water carnival bathing suit. As a testament to his young prowess, he once defied the watchful eyes of wartime military policemen assigned to guard the river’s railroad trestle. Fred climbed to the top of that structure and took a half pike swan dive into the shallow river below. Hundreds of onlookers marveled at his skillful feat. However, once his dad found out, it meant the end of Fred’s trestle hijinks.

The impresario of the water carnivals was Skip Littlefield. He was a collegiate swimming champion and naturally at home in the water. After being an early carnival performer for nine years, in 1936, he became director, choreographer, and promoter of the shows. Soon after that, the exhibition became nationally famous. Swimming experts considered it the most excellent amateur aquatic show in the nation. It grew to include top professional vaudeville acts as well as some of the world’s greatest swimmers, along with pre-teen and teen amateurs. Skip reveled in the publicity he garnered for these events along the West Coast and all the way to New York.

Fred described Skip Littlefield as the charismatic “man in charge.” Quadros recalled that rehearsals occurred on Thursday evenings during the summer season, once the plunge was cleared of public bathers. Showtime commenced at 9:00pm the following Saturday. Minutes ahead, participants gathered around Skip to learn the order of their acts and his cue to begin them. Littlefield then announced and described each feat to a full house of 1,600 spectators.

By the age of 12, Fred was a star diver, a fantastic accomplishment for this young man. He was one of nearly three dozen performers in the weekly spectacles. I’m guessing that musicians were included in that count. Carnival-goers enjoyed band music and soloists on those festive evenings, too.

Walk into the old plunge building where Neptune’s Kingdom is today. Look up at the eight light-blue, century-old arches still upholding the building’s barrel roof. It’s a new roof with original arch supports. In your mind’s eye, picture young Fred ascending the western-wall platform. Imagine him slowly making his way up to and then across the first arch at the Casino end of the building. Standing on the lower lip of the arch at a centered spot over the deepest section of the pool, he’d survey the water about 70-feet below.

From that height, Fred said it could be hard to mentally assess the location of the water’s surface. A slight ripple from a hose of jetted water improved its discernibility. Fred planted his feet on the arch lip and studied the pool below. He would then crouch so that when propelling himself forward in a majestic swan dive, his head would not hit the ceiling. It hurt to enter the water from that height, he recounted. His arms would fly backward until he could gain control of his underwater movement back to the surface.

At one point, Littlefield had a hole cut in the center roof of the plunge to make daredevil dives even more dramatic. Quadros remembered he once made a rooftop launch through that opening, nearly 10-feet higher than the support arch.

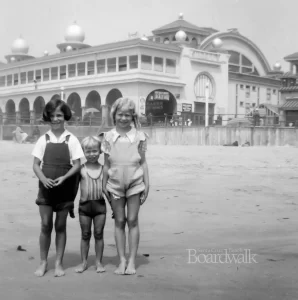

High above the balcony level of the plunge on the western building wall stood several deck stages. The longest rested about 20-feet higher than the balcony. Several smaller platforms lay another 15-feet higher. Fred and others used these perches to commence spectacular artistic dives into the pool’s deepest section and to take off on their flying trapezes. News accounts of that day are full of these water carnival exploits.

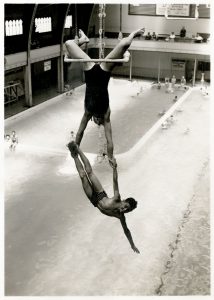

The “Aerial Human Triangle” became a high point of the nightly exhibition. Fred starred in this act and Santa Cruz Sentinel pressman Don “Bosco” Paterson was also a mainstay. Hanging by his knees on a catch bar, Bosco would grab two young “aquabrats” – one at a time – after each leaped in turn from a flying trapeze into his secure handhold. He would catch the first in one hand, followed by the other in his remaining grip. These two young lads would then join their spare hands, forming an aerial triangle with Bosco. Then Freddie would swing on his trapeze toward his partners, letting go at just the right time to leap and pierce through the human triangle and dive into the pool 25-feet below. The feat was a real crowd-pleaser.

Littlefield promoted a very young Shirley Wightman to be the act’s catcher at times. Being only a few years older than Freddie, she was not always able to readily grab aerial “aquabrats.” When necessary, several lads would shimmy down some ropes from a catwalk high above her to grab hold of Wightman’s hands and form their triangle. Then Freddie would swing through the air and fly through.

Quadros recounted he did not always make a clean pass, likely causing the whole human affair to drop into the pool. He said the crowd still roared with glee when this occurred. If there happened to be three unsuccessful attempts, always with cheering crowds, the stunt would be called off until the following week’s performance.

The water carnivals stopped near the end of World War II. Fred humorously mused that if there was OSHA back then, the festival would have been shut down. To top things off, he said he and the other young, amateur performers were not paid for their performances, as were the professional participants. But he did get free access to the Plunge every day and the local fame around town of becoming known as “Fearless Freddie” Quadros.

Does anyone have any memories of the water carnivals? I’d be pleased if you would share them.

’till next time,

Ted

Archives@beachboardwalk.com