Boardwalk entrepreneur Fred Swanton always dreamed big. In June 1906, after an early morning fire consumed his 1904 Moorish-styled Casino complex at Santa Cruz Beach, he immediately organized the design, financing, and construction of a more elaborate second Casino and Natatorium to open in June 1907.

His next vast Boardwalk undertaking was commissioning a Scenic Railway, a unique gravity coaster the likes of which enjoyed rising popularity throughout the country. Unfortunately, the ride never fulfilled the vision of Swanton or its builder. Read on to learn the saga of the lack-luster ride that preceded the Giant Dipper.

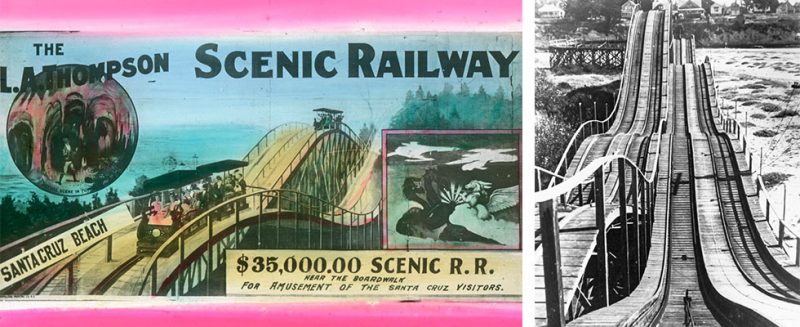

Our archives reveal conversations occurring as early as August 1907 with an agent of the L. A. Thompson Scenic Railway Company regarding establishing a ride on the easternmost sector of the Boardwalk. In April 1908, the Santa Cruz Evening News announced that Fred Swanton approved a contract for the Thompson Company to develop one of its novelty rides at Santa Cruz Beach. I surmise Swanton’s proven persuasive negotiation skills sealed the deal to secure this sizable addition to his beachfront.

The first authentic American roller coaster was the brainchild of LaMarcus Adna Thompson. He built his gravity coaster, called the Switchback Railway, for Coney Island, New York in 1884. His contraption was hugely acclaimed, and ambitious rivals soon appeared. According to Theme Park Insider Magazine, within four years, Thompson had built 50 of his coasters across the United States. That’s a lot of expansion back then and speaks to the rapid popularity of these new-fangled rides.

While his rivals focused on producing bigger and faster coasters, Thompson went another direction. By 1888, he started adding visuals to his rides—first tunnels and lights, and then scenery—all of which proved uniquely popular on his “scenic railways.”

While his rivals focused on producing bigger and faster coasters, Thompson went another direction. By 1888, he started adding visuals to his rides—first tunnels and lights, and then scenery—all of which proved uniquely popular on his “scenic railways.”

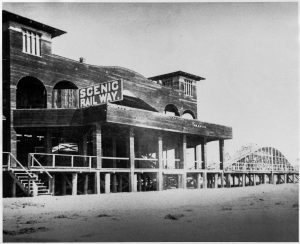

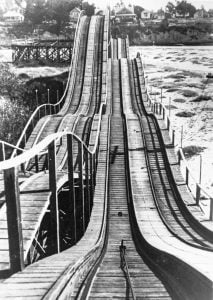

Construction of the Boardwalk’s Scenic Railway began in spring 1908, the second one for the Thompson Company on the West Coast. An article on the front page of the May 31, 1908 Santa Cruz Morning Sentinel stated the structure paralleled the railroad right-of-way toward the San Lorenzo River. It will “make a curve more thrilling and complex than ever has been attempted by a scenic road, a new trick in the trade. The route will continue to the river and back several times before the ride is completed.” The article went on to state, “There will be no tunnels on the road this year. There will be plenty of novelty without tunnels for this season. But before another season arrives huge tunnels will be erected along the part of the road near the mouth of the river, and in these tunnels, wondrous panoramic scenes will be depicted with striking realism.”

The Thompson Company never built those elaborate tunnels. While printed news accounts, then as now, can be loose with facts, the reported intent of the builder is consistent with that company’s style of roller coasters. The failure of this scenic ride element to materialize piqued my curiosity.

The Thompson team estimated total construction cost at $35,000, around $975,000 in today’s dollars. Its contract required that Santa Cruz workers perform all labor. Even its trains were made locally, adhering to Thompson patents. The double-tracked arrangement was longer and swifter than any in the Thompson Company’s family of coasters. It stretched over 1000-ft. Two trains holding 30-passengers each operated at the same time during the 4-minute circuit – twice over the track’s entire length, encompassing about a mile altogether. A brakeman rode at the rear of each train and controlled speed with a manually operated brake. Even though the ride’s 25-mph was fast compared to autos that traveled just 10-mph back then, speed and thrills were secondary to the overall ride experience.

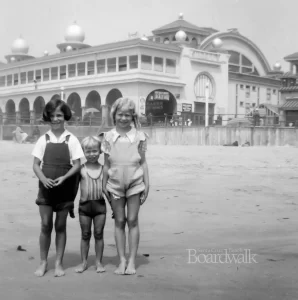

Our Scenic Railway opened to the public on schedule, July 1, 1908. Within a few weeks, it was the star attraction at the beach. By August, Southern Pacific Railroad advertisements appeared in San Francisco newspapers promoting seven full hours of fun at Santa Cruz Beach. Special Sunday excursion trains departed from both San Francisco and Oakland. The ride’s popularity was off to a splendid start.

Reviewing Boardwalk archival files further aroused more of my curiosity. I found the L.A. Thompson Scenic Railway Co. sold its rights, leases, and buildings to the Santa Cruz Beach Company on July 1, 1911—for $1. The Beach Company initiated an agreement further releasing the L. A. Thomson Company for any claims and liability associated with the ride that might arise.

Three years to the day after the ride’s public unveiling, the Thompson Company wanted to move on and sever its association with its Santa Cruz project. No archival records elaborate further on this decision. We do have the actual Bill of Sale and General Release documents which delineate the Thompson Company’s separation from its ride. It would be helpful to review the original 1908 lease for the ride, but, alas, I have not located that document. The ride’s $1 sale price to the Beach Company suggests the Thompson Company desired a quick transfer.

I haven’t found any local news coverage back then that offered more insight on the exchange. Even early Boardwalk historian Skip Littlefield left no clue in his papers. Why would the Thompson Company abandon its ride so soon, I wondered?

In my further investigation, I found a 1912 map showing the easternmost reach of the ride extending very near the San Lorenzo River. A 1920s aerial photograph substantiates the same. Skip Littlefield’s notes state the east end of the Scenic Railway needed replacing because of high tides and a rampaging river in January 1910 and again in the winter of 1911. The eastern end of the ride was not constructed to withstand raging winter river torrents and high tide storm surge, regular features at the mouth of the San Lorenzo River. Most likely, this clarifies why a scenic tunnel element never turned up on the ride.

A search through some Los Angeles area newspapers reveals another clue to the Thompson Company’s abrupt departure. Soon after launching its Santa Cruz coaster, the L. A. Thompson Company became active in ride development in southern California. It built its most elaborate scenic railroad in April 1910 in Venice, CA. Regarding the company’s $60,000 investment there, the Los Angeles Herald stated in March 1910, “The track will wind among high mountain peaks, through dark canyons where only the stars may be seen overhead, across yawning chasms and past rushing mountain torrents.”

Then the Los Angeles Times announced a year later in April 1911 the Thompson Company’s second scenic railway in the southland. For $250,000, “Dragon’s Gorge” opened at Ocean Park in the Santa Monica area. This ride even simulated an active volcano by ingeniously using electric bulbs and appliances for that time. In May, that paper reported crowds converging on that ride.

A few weeks later, the Thompson Company surrendered its Santa Cruz project.

The Thompson team must have seen tremendous potential for more Southern California ride development. That areas milder weather blessed the prime summer months and increased business on spring and fall shoulder seasons. The large population base in the Los Angeles basin enjoyed an expanding public trolley system for convenient transport of thrill-seekers to and from burgeoning entertainment meccas along the coast and throughout the region.

By contrast, Santa Cruz beach business sprinted through a short season from Memorial Day to Labor Day. Visitors from our more distant market area surrounding San Francisco Bay relied on railroad transportation to and from Santa Cruz, a trip of several hours each way.

I speculate that the unexpected annual expense of winter storm repairs cut too deep into the Thompson Company’s summer profits at Santa Cruz Beach. Understandably, the Thompson Company’s enthusiasm for its Santa Cruz Beach project would dwindle in favor of more robust activity in the south.

Two years later in 1913, Fred Swanton left the Beach Company he pioneered. That company and its successor Santa Cruz Seaside Company navigated our Scenic Railway through struggling economic years from 1913 to 1916. The ride did not operate in 1915.

Annual ride maintenance flexed in response to the toll of nature’s winter fury. Boardwalk management added a tunnel to the ride in 1919 to build intrigue. Nothing shows it was ever more elaborate than a simple tunnel.

The tired and worn ride longed for revival when in 1923 Arthur Looff proposed razing it and installing a new roller coaster in stride with the roaring 1920s. Beach management accepted Looff’s offer. In early 1924, the Seaside Company quickly demolished the Boardwalk’s Scenic Railway and the Giant Dipper roller coaster opened to the public on May 17 that same year. The Dipper’s easternmost structure stayed clear of the San Lorenzo River, benefiting from its predecessor’s experience.

In the early 1960s, a concrete seawall was constructed around the east end of the Boardwalk to successfully withstand the ravages of winter storms. This area is fully built out today with many rides and activities that appeal to today’s visitors.

-till next time!

Ted

archives@beachboardwalk.com