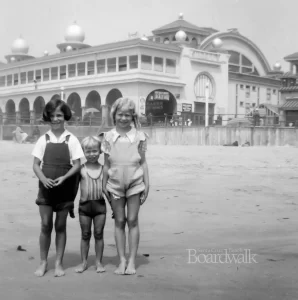

“If you build it, they will come” was not one of Fred Swanton’s entrepreneurial maxims. His vision for the success of the Santa Cruz Beach Company’s 1904 and 1907 Casino complexes included personally extolling the benefits of his “Coney Island of the West” throughout California.

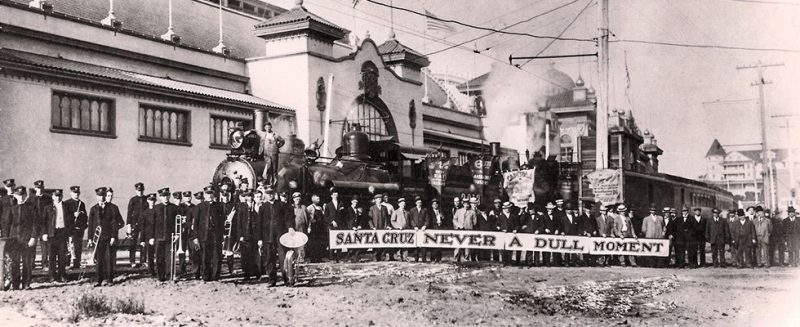

Each spring, from 1904 to 1912, Swanton took his “Never a Dull Moment” message straight to prospective vacationers. He filled a special Southern Pacific train with local business people, brass bands, entertainers and loads of souvenirs and headed off on a state-wide tour to promote Santa Cruz.

Fred could promote as enthusiastically as he envisioned and built things. In 1905 the Fresno Evening Democrat described Swanton as possessing “scientific knowledge of the art of advertising.” Referring to Swanton’s winning personality, the paper further noted, “He has gone into the work heart and soul, and results show he surely believes in the present and future of Santa Cruz.”

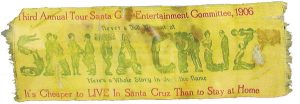

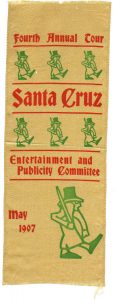

Ahead of each summer season, Swanton organized a band of Santa Cruz citizens, mainly business people who stood to profit from increased summer business, to accompany him on a whistle-stop train excursion to targeted cities. His varied itineraries stretched from Redding to Santa Rosa to Colfax to Bakersfield and Los Angeles—even to Reno, Nevada. Townspeople called the group the Santa Cruz Entertainment Committee or Promotions Committee. The common name for this group became the Santa Cruz Boomers. Their train became the Boomer Train.

Southern Pacific, an early investor in Swanton’s beach megalopolis, eagerly provided the train and a schedule adapted to the promotion committee’s annual plan.

The Boomer entourage varied in scope each year. One news account refers to 24 attending and another to 40 and another to 60. Swanton had contracts with the 13th US Infantry Band from Angel Island and the 3rd US Artillery Band from the Presidio of Monterey. He occasionally enlisted and augmented the Santa Cruz Beach Company band to fill in. These musicians accompanied Swanton and alternately became pillars of community celebrations at Boomer train stops. Each excursion cost around $8,500, even with individual Boomers paying their way. One news outlet reported Swanton could raise that sum in 5-days.

On May 7, 1907, as Swanton‘s second, more substantial and more elaborate Casino and Natatorium neared completion, his company of promoters met in the heart of central Santa Cruz. They began their 11-day foray into California’s heartland at 8:00am. The 3rd Artillery Band led the civic boosters down Pacific Avenue while a 5-person drum corps contingent beat cadence from the rear. At the depot, a special train awaited its passengers. The baggage car was full of 50,000 badges, 20,000 matchboxes, 6,000 ribbons, and 20,000 Santa Cruz Beach visitor guides along with the paraphernalia for making merry, all given away during the trip. A dining car, tourist sleeping car, and a Pullman sleeper completed the consist. The name “Swanton” emblazoned the sides of the last car.

The exclusive and fraternal nature of Boomers, at least in one year, required that no fellow could sport a mustache. Unsuspecting Boomers came aboard that year to learn of their fate. The resident Casino barber gave a fresh shave above the lip over any victim’s protestations. Even Armond Putz, the officious military officer and conductor of the 3rd Artillery Band, was unwillingly and unceremoniously subjected to this slight.

Communities made a big deal of the Santa Cruz troupe’s arrival. Some towns even requested a visit so as not to be left out of the festivities. Precise planning characterized these excursions. For bigger cities, several advance men visited a few days ahead to set matters in order. For smaller townships, letters, telegrams, and in some cases telephone calls, initiated preparations for Swanton’s arrival.

Delegations of host community citizenry attended the arriving train and festivities began at their depot. After a 1905 Sacramento arrival, the Boomers found themselves in friendly competition with a circus parade already in progress. California Governor Pardee invited Swanton to the State Capitol and requested the military band give a concert in the Senate Chambers to state dignitaries and their families—a real first! Two years later, Swanton chartered a Sacramento streetcar festooned with banners heralding their next day’s arrival.

A lively reception occurred in Los Angeles in 1907. That year Swanton chartered two electric streetcars. He put the band in one and his enthusiasts in the other with plenty of souvenirs to toss to bystanders. Even in this more established tourism mecca, Swanton’s team got recognition. On a subsequent visit, purveyors of Southern California attractions prevailed on local newspapers to stop giving Swanton the headlines and column inches of publicity they previously devoted to the Santa Cruz assemblage.

In 1910, the mayor of Santa Rosa met Swanton at the depot with a large tin lid inscribed, “The lid is off in Santa Rosa for the Santa Cruz Boosters.” That same year, the group’s two-block-long procession in Oakland had a festooned megaphone man announcing the parade, shilling the crowd and proclaiming, “Hold on to your horses.” Then came Swanton and Oakland’s Chief of Police. The Santa Cruz Beach Band – 22-members strong – picked up the pace just ahead of the 30-ft long “Never a Dull Moment” banner, held aloft by the hands and arms of 3-participants.

The first segment of Boomers followed and jovially accosted onlookers until each proclaimed their resolve to come to Santa Cruz on vacation. A strolling quartet harmonized, eager to be heard above the trailing regimental band of 20-players. The second section of Boomers came next and handed out souvenirs, buttons, and other memorabilia street watchers could not decline. Santa Cruz baseball players, united with their Oakland counterparts, brought up the rear in automobiles. Festive banners accompanied the exhibition.

Thousands of souvenir items found their way into observers’ hands. Some Boomers, gifted with gab, called themselves “spielers.” They recited a scripted spiel to individual onlookers one-by-one. They playfully would not concede until that spectator exclaimed, “I’ll come to Santa Cruz on vacation.” Santa Cruz boosters celebrated all day and frequently well into the night. Fireworks enlivened evening festivities. Also, a stereopticon contraption displayed projected images of Santa Cruz and especially of the Casino and Natatorium complex.

The Modesto Herald reported of the Boomer’s 1905 visit, “Mr. Swanton is a jolly good fellow and is at the head of a good aggregation. He is furnishing towns like Modesto with a good day’s entertainment, and he is making it pay. We will all go to Santa Cruz this summer.” The Grass Valley Tidings reported that year, “Swanton thoroughly understands his business, and Santa Cruz will be heralded throughout California at least as the most wonderful city in the West.”

On a day when a series of rapidly successive whistle-stops occurred, Boomers worked in relays—one group in one community and another the next. Energy remained high. Never wanting to sour local sensibilities, Swanton accommodated his schedule of events to coordinate around, and even help support, other community groups that competed for hometown attention during his visit.

In 1911, the longest train ever, carried his troupe to sixty cities. It consisted of a baggage car for souvenirs, fireworks and promotional guides and giveaways, three Pullman cars—one for each band and a few traveling advertising men and the other for his twenty-four committee members—then came a dining car and an observation car. A train crew of 22 serviced the lot en route.

At the close of a tour, Swanton arranged for his train to return to Santa Cruz at a precise pre-publicized time to ensure a suitable number of local townspeople were on hand to welcome the tired bunch home. Then the entourage would march from Santa Cruz Depot up Pacific Avenue, just like one of their out-of-town visits, to stoke hometown acclaim for the group’s promotional success.

In 1912, Santa Cruz caught a chill from the winds of a national economic recession. A declining number of visitors meant less spending overall that year. Although management denied it, late in the year rumors began circulating that Fred Swanton was leaving the Beach Company. Then it happened. In early 1913 Fred took a position in banking. However, in a couple of months, his notoriety for showmanship engaged him with those planning for the 1915 Pan Pacific Exhibition in San Francisco. Swanton’s association with the Beach Company slowly faded away, as did many of his investor’s dreams.

An air of alarm set in among Santa Cruz business folk fearing that the Boardwalk might declare bankruptcy. Exuberance for the Santa Cruz beachfront diminished and Boomer trains ceased to run.

‘till next time –

Ted

archives@beachboardwalk.com