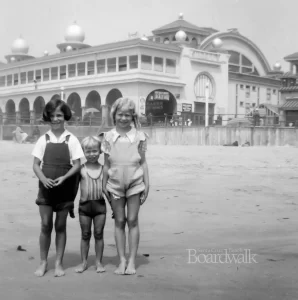

What does an independently owned, traditional amusement park do when a giant theme park enters its marketing area? Many simply went out of business in the 1960s and 1970s. Not so for the Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk.

In 1976, Marriott’s Great America opened in Santa Clara, CA, just 40-miles north of the Boardwalk. Revenues flattened that year at the Santa Cruz beachfront, a result of that new park’s unique appeal to Northern California amusement park-goers. Boardwalk management knew the right new ride would help bolster revenues. That ride would need to enhance the Boardwalk’s family-friendly appeal, too.

We had our iconic Giant Dipper roller coaster and there really wasn’t room for another coaster. So we focused on adding an innovative experience – a flume ride – as the perfect addition.

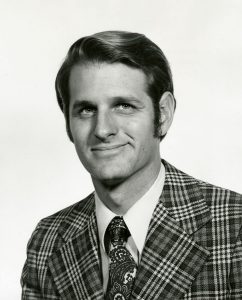

Making such a ride fit within the Boardwalk’s small footprint was tricky. Seaside President Laurence Canfield was several years ahead of the challenge, though. He hired Dana Morgan, a uniquely qualified general manager in 1975.

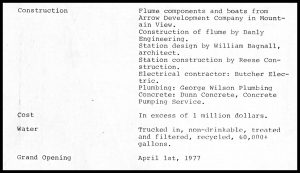

Morgan’s father was one of the founding partners of the Arrow Development Company that provided the Boardwalk with its Cave Train and Autorama rides in 1961. Arrow was also the premier manufacturer of flume rides in the mid-1970s. Dana Morgan grew up in that ride-building world and had already supervised the installation of flume rides in many amusement parks throughout the country. If anyone could make a flume ride fit at the Boardwalk, he could!

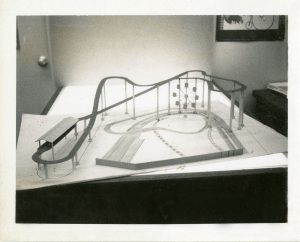

The east end of our park along the San Lorenzo River was the only practical area for such a ride. Dana went to work with Arrow Development engineers to design a flume for that space. As with any of these elevated water rides, the critical design path became the length needed for its down ramp and the splash pond runout. Experience demonstrated that creating a sufficient length for these vital segments would dictate the ride’s engineering success. At the Boardwalk, adequate length for these segments could be achieved if the elevated flume trough traversed above the railroad tracks that border the north boundary of our park. With that arrangement, Arrow’s engineers conceived of a flume that would fit!

Fate then took its first fickle turn. The Boardwalk’s decades-long history of minor encroachment into the railroad right-of-way that borders the park had always been approved by Southern Pacific Railroad. Thinking that, once again, the railroad would routinely grant its permission, the finalized flume design plan was presented to the branch line overseer as the last hurdle. To our surprise, this time, Southern Pacific officials had no problem saying “no” to the overhead encroachment without giving any real justification for the decision.

Here’s where the story gets more interesting. Now that we knew a flume could be made to fit within the constraints of the Boardwalk’s eastern end, Morgan would not take Southern Pacific’s “no” without a challenge. In a fortuitous arrangement, in the mid-1970s, Arrow Development was owned by a subsidiary of the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad. Validating the adage that it’s not what you know, but who, Dana Morgan had previously met the president of the Denver and Rio Grande. Dana called his office to solicit help in negotiating Southern Pacific’s approval. In just two days, Morgan received a significant telephone response. The caller, an incredulous Southern Pacific mid-management official, abruptly stated, “Your project is approved.”

With that major hurdle overcome, our large flume could become a reality. Unfortunately, the ride’s station could only be located where our beloved Wild Mouse resided. Since 1958, the Wild Mouse gave its riders spine-tingling memories that live to this day. However, our new water ride appealed to the family demographic the Boardwalk courted, more so than our rip-roaring compact coaster. Sadly, that coaster had to go, and it became an easy decision to remove “the Mouse.”

After a year-long construction planning and permit approval period, we received the necessary authorizations. I remember watching the construction of the ride’s towers and elevated channel begin in October 1976, all 1,200-feet of it. The loading and unloading elements were installed at the base of the station platform, as well. Week by week, the ride took shape as it morphed toward its final dimensions.

Construction proved more difficult than expected, though. Some tower foundations became easily flooded by the winter river and sea surge. This water intrusion made a delicate matter of pouring their cement foundations and the subsequent removal of sleeves that formed the concrete. Twice the cement became necessary to make some foundations firm. Several towers penetrated down into the river basement, necessitating the Cave Train’s track be reconfigured around them. Topside, the Autorama speedway had to jog a little to negotiate around a column or two. Gradually, the 55-foot high trough began to dominate the Boardwalk’s eastern ride scene.

In January 1977, construction of the ride’s station began. Being a “log flume ride,” the company took an extra step to salute Santa Cruz County’s historic logging industry by making the station resemble a sawmill. The ride also paid homage to a fabled 14-mile long San Lorenzo flume that was built in the 1870s, deep in the Santa Cruz mountains.

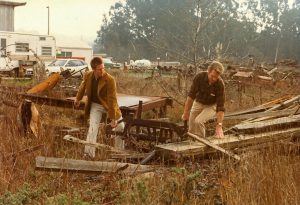

To authentically replicate the feel of a hundred-year old sawmill, Dana Morgan, and Seaside Company Vice President (at that time), Charles Canfield sought advice from the McCrary brothers, owners of the local Big Creek Lumber Company, and well-known in local logging circles. Then, the duo set out to find appropriate artifacts to realistically outfit the station’s interior. Canfield and Morgan flew to Eureka, California to begin their quest. They traveled through nearby homesteads and farms, finding and buying old, rusted, even broken logging wood-working artifacts. Perplexed north coast old-timers marveled at the good fortune their junk afforded them. A rented U-Haul truck, filled with this historical treasure, returned to the Boardwalk. Piece by piece, turn-of-the-century equipment and artifacts outfitted the ride’s station. The building began to look like an old working sawmill.

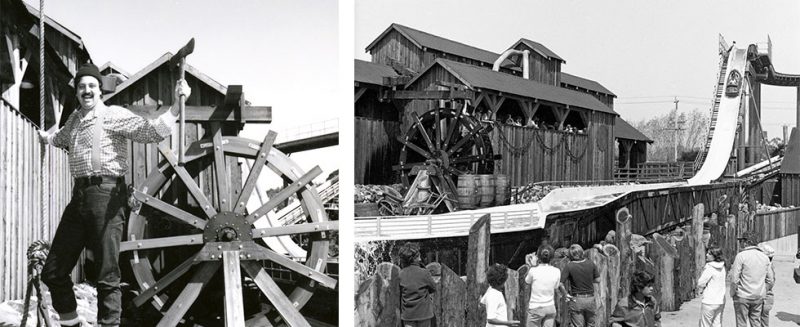

An authentic 14-ft water wheel became an appropriate station exterior addition, complimenting the ride’s show and splash pond. Interestingly, the central Babbitt bearings for that wheel came off the original drive wheel of our 1924 Giant Dipper Roller Coaster. They still serve as the primary bearings for the water wheel today.

Then, once more fate evidenced its fickleness. With the ride’s scheduled opening on April 1, 1977 looming, California and Santa Cruz were responding to the effects of a severe 2-year drought. In fact, a Santa Cruz city water rationing program commenced in early March 1977. Our ride needed about 60,000 gallons of water in its holding tank to successfully operate its 24 log-themed boats, each with a capacity of 4 guests.

The ride could have been filled with city water before the rationing ordinance’s commencement. However, as a public relations gesture, Boardwalk officials decided not to connect to the city’s system. Instead, arrangements were made with a coastal farmer to use slightly brackish water from one of his ground-water wells. A series of tanker-trucks transported that water to the Boardwalk and filled the ride’s holding tank, where it was filtered and treated for its safe use on the ride. Two 250-horsepower pumps could power 24,000 gallons of water per minute up the incline to the ride’s trough. Log boats could now begin their scenic float along the winding channel, high over the railroad tracks, eventually to the spillway and return to the station. The water itself would return to the holding tank.

Steel girders supported the flume’s track and trough in the pond. Although partially underwater, they needed to be disguised so as not to detract from the millpond scene. Someone got the idea of setting lava rocks about the trusses as the perfect camouflage. These worked great until the pond was filled and we learned that lava rocks float. Construction workers quickly rescued the bobbing rocks and cemented them firmly in place, which did the trick.

A few days before the ride’s opening, an unveiling was staged for local media. I watched and listened as skeptical reporters and politicians received multiple assurances that no city water was being used on the flume. Some were hard to convince, even after Charles Canfield’s continual assertions. However, they did learn the ride’s water was within a self-contained system and needs only minimum refilling for spillage and evaporation – just like a swimming pool. All were assured our ride would open with salt-tinged groundwater, adequately filtered, and treated – and it did! Signage advised guests of the rasty-looking water’s safety and non-potability.

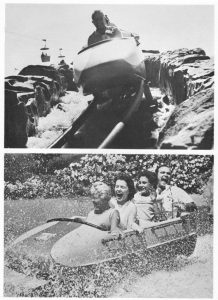

On April 1, 1977, Boardwalk logging personality “Big John” welcomed guests to the opening festivities. Logger’s Revenge debuted as a fundraiser for Dominican Hospital. Santa Cruz Mayor John Mahaney and Dominican’s Sister Josephine rode to a splashing finale in the first official log, cheered by local dignitaries and civic leaders. The ride then filled to full capacity, carrying 1,300 people per hour on its 2 ½ minute scenic and soggy journey. I was one of those lucky ones!

On April 1, 1977, Boardwalk logging personality “Big John” welcomed guests to the opening festivities. Logger’s Revenge debuted as a fundraiser for Dominican Hospital. Santa Cruz Mayor John Mahaney and Dominican’s Sister Josephine rode to a splashing finale in the first official log, cheered by local dignitaries and civic leaders. The ride then filled to full capacity, carrying 1,300 people per hour on its 2 ½ minute scenic and soggy journey. I was one of those lucky ones!

Logger’s Revenge has delighted families for 40-plus years. Now you know the fascinating story of why and how our Logger’s Revenge ride entered onto the Boardwalk scene.

-till next time –

Ted